The first time I heard the phrase “flyover country” I was a young teenager living in the heart of it: Gypsum, Kansas, population 365. We had a post office, gas station, bar, hardware store, a five-and-dime, and one neighbor for every day of the year. The longest highway in the state, KS-4, doubled as our main street.1

My mom owned a restaurant in Gypsum called The Restaurant (it was the only one in town). During the summer, my brothers and I took turns working shifts there. I timed my breaks so I could sit with the farmers who converged mid-morning to drink coffee and eat one of my mom’s World Famous Cinnamon Rolls. The men would comment on the passing cars, talk about what was happening on their farms, complain about the rain when it was raining, and pray for rain when it wasn’t. I already knew I wanted to be a writer, but it was at The Restaurant, with those farmers, and those cinnamon rolls, that I decided to write about rural people and rural places.

I loved Gypsum. There was more than enough scope for even my hyperactive imagination. In 2022, I wrote a piece for Strong Towns that riffed on the opening song of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, the animated version of which came out when I was thirteen and living in Gypsum. The article was called “I (Don’t) Want More Than This Provincial Life.” Reflecting on growing up in a small town on the Kansas prairie, I wrote:

Like Belle, I wanted adventure, but it never occurred to me I needed to leave town for “the great wide somewhere” to find it. I dreamed in fairy tales, but they weren’t set in distant forests and foreign castles; I just assumed that Gypsum Creek, and the fields of winter wheat, and the abandoned high school, were crowded with their share of fairies and gnomes and ghosts.

To be provincial means to be outside the capital. In ancient Rome, a provincia was a territory under imperial domination; it was a place that had been conquered. Today we use the word provincial as a synonym for narrow-minded, unsophisticated, countrified. But I never minded being countrified, any more than I minded my steak chicken fried.

While I could reclaim the word “provincial,” it was the phrase “flyover country” I truly resented. I was offended by the implication that the people and places I loved, and found endlessly fascinating, were an afterthought, an interlude to be endured on the way to somewhere more interesting. Watching a distant jumbo jet arc across the sky I would think to myself, “They don’t know this place. They don’t know what it’s like down here. They don’t know our people.”

Even now, more than thirty years later, living in Oregon with my family, I feel an abiding solidarity with the rural Midwest. When I see news stories of tragedies there—a devastating tornado, for example—there’s still a part of me that thinks, “I should have been there. I should be there now. Those are my people.”

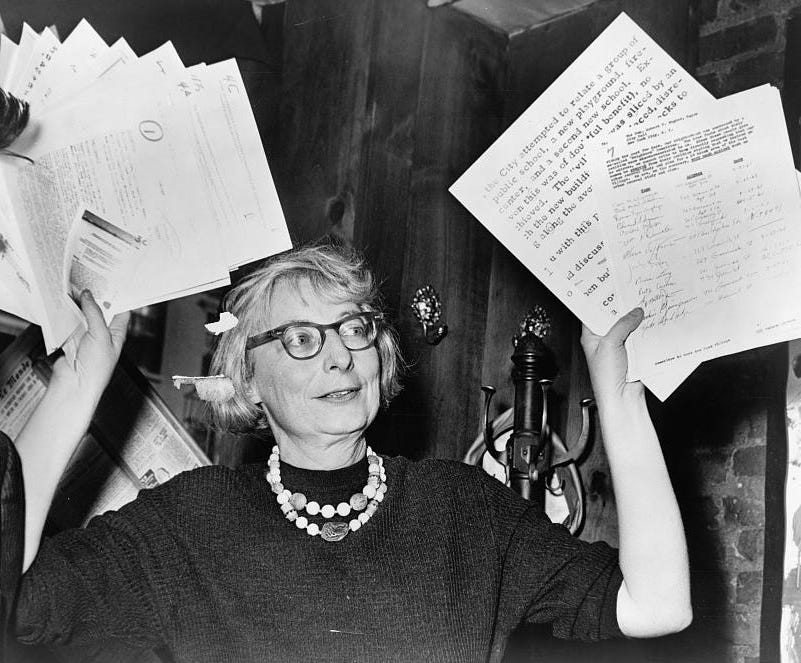

Last weekend I watched Citizen Jane: Battle for the City, a documentary about a series of clashes in the 1950s and ‘60s between Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs.2 Moses was a graduate of Yale, Oxford, and Columbia, an urban planner, and a public official of almost unrivaled power in New York. Jacobs was a largely self-taught journalist and urban theorist whose 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities would become a classic text and an inspiration to many thousands of people—including us at Strong Towns.

Moses had impressive stamina. He worked 16-18 hours a day. At his peak, he held 12 different offices. Under the banner of “urban renewal,” he transformed New York. Oliver Burkeman, writing in The Guardian, says, “You needn’t care especially about New York to be awed by the changes Moses wrought there: during a 44-year reign, he built nearly 700 miles of road, including the giant highways that snake out of the city into Long Island and upstate New York; 20,000 acres of parkland and public beaches, plus 658 playgrounds; seven new bridges; the UN headquarters, the Central Park zoo and the Lincoln Center arts complex, racking up expenditures of $27 billion, dwarfing any previous run of construction in US history…Around 500,000 people, who happened to find themselves in the way of Moses’s vision, were evicted from their homes.”

Not all of Moses’s schemes were successful. He played Goliath to Jacobs’s David on projects that would have made large swaths of Manhattan unrecognizable today. One was his plan to turn Washington Square Park, in the heart of Greenwich Village, into a four-lane highway. Jacobs, an editor and freelance journalist who lived in the West Village, rallied the neighborhood to successfully kill the proposal. At one public meeting, Moses lost his cool and said, “There is nobody against this—NOBODY, NOBODY, NOBODY but a bunch of…a bunch of MOTHERS!”

The larger battle between Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs—and a debate still very much happening today—was about who gets to shape our towns and cities.

Some of the most striking scenes in Citizen Jane are of urban planners striding, as giants, around room-sized models of New York City. The author and historian Thomas Campanella says, “The planners conceiving these urban renewal projects [were doing so] from that godlike vantage point in the sky.”

Robert Moses was a disciple of Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French modernist architect and planner whose utopian vision for central Paris would have demolished its medieval and 19th-century buildings and replaced them with glass office skyscrapers. Campanella says in Citizen Jane that the gestation of Le Corbusier’s ideas came as a result of riding in an airplane over Paris. “Before the wheels hit the tarmac he’s concluded that we need to sweep all this away and rebuild our cities.”

I found a PDF of Le Corbusier’s 1935 book Aircraft. He says the airplane indicts the city. “Cities, with their misery, must be torn down. They must be largely destroyed and fresh cities built.” This was the way to bring cities into “the new era of machine civilization.” Corb writes: “Technicians of every contemporary activity be not dismayed or discouraged. Make plans, make plans. There is no such thing as rash or chimerical plans : plans are truths.”

Le Corbusier preached the separation of uses—commercial, residential, recreational, industrial—called for city centers to be torn down and rebuilt and the suburbs to be pushed even further out, and he prioritized speed over almost everything: “A city made for speed is a city made for success.” His means of realizing his vision can be charitably described as authoritarian, and he once dedicated a book “To Authority.”

While Corb’s modernist vision was largely rejected in Europe, it found purchase in North America in urban renewal and the suburban development pattern. For decades, the face of this approach was Robert Moses, whose sway extended far beyond New York. The great urbanist and architecture critic Lewis Mumford once said, “In the 20th century, the influence of Robert Moses on the cities of America was greater than that of any other person.” Still today, the suburban development pattern remains the default approach to building towns and cities in North America.

Watching Citizen Jane it struck me that, for Le Corbusier and Robert Moses and the approach to city-building they personified, every place is “flyover country.”

From an airplane or helicopter, or standing over a diorama of the city, neighborhoods become abstractions. Max Page, a professor of architecture, says in the documentary that, looking down from on high, Moses and Corb were “able to imagine massive transformations.” I’d go further and say that, at that distant scale, only massive transformations are imaginable.

Jane Jacobs reversed the vantage point.

Robert Moses may have been a visionary but it was Jane Jacobs who could really see. If Moses was the “eyes in the sky,” Jacobs was all about the “eyes on the street.” Where Le Corbusier saw a machine, Jacobs saw an organism. In Death and Life, she described cities in the language of biology, as organized complexity: “The variables are many, but they are not helter-skelter; they are ‘interrelated into an organic whole.’”3

After watching Citizen Jane, and in honor of Jane Jacobs Day on Sunday, I re-read Jacobs’s famous 1958 essay, “Downtown Is for People.” Its premise is that “the best way to plan for downtown is to see how people use it today…There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”

Jacobs is critical of the downtown redevelopment projects, and what she called “the project approach,” that were ruining downtowns across North America. “The architects, planners—and businessmen—are seized with dreams of order, and they have become fascinated with scale models and bird’s-eye views.”

The planners she criticized were thinking in terms of blocks not streets, and of prototypes not people. The project approach isn’t rooted in the day-to-day stuff of life; it deals with reality only in a vicarious way, says Jacobs. The alternative approach is as simple as it is profound: “You’ve got to get out and walk.”

Jacobs ends her essay by calling all citizens to get involved. She is writing about downtowns, but the sample principles hold true in every neighborhood and in towns and cities of every size:

The remarkable intricacy and liveliness of downtown can never be created by the abstract logic of a few men. Downtown has the capability of providing something for everybody only because it has been created by everybody. So it should be in the future; planners and architects have a vital contribution to make, but the citizen has a more vital one. It is his city, after all; his job is not merely to sell plans made by others, it is to get into the thick of the planning job himself.

Jacobs isn’t saying everyone needs to go out and get degrees in architecture, planning, or engineering. Far from it. She’s calling on the residents of a place to get out and walk and to ask questions. She gives examples but sums up all the questions this way: “Will the city be any fun?”

I haven’t been back to Gypsum in years. Last time I was there, many of the downtown buildings were boarded up. Scanlan Hardware Store had closed. The five-and-dime was gone. The sidewalks were emptier than I remembered. The first thing that greeted a visitor to downtown was a self-storage facility. The bar was still there. The Restaurant was still there too, though it has a new name.4

Sometimes I tour Gypsum on Google Maps, knowing that this is its own kind of flyover experience (and that Google hasn’t bothered to re-map the town since 2014). I catch myself making plans and having ideas, but then I remember: I’m the stranger now. I can’t actually know what is going on there.

If Gypsum has a bright future, it will not come from an outsider like me but from the inside. It won’t be the work of a single visionary, but from the people who live there and who love it. They love it not only for what it could be but for what it was and for what it is now.

While I was born in Oregon, and live there again today, my dad’s job as an air traffic controller settled the family for many years in the Midwest.

I’m grateful to my friend Steve MacDouell for recommending this documentary.

At Strong Towns we like to say that top-down thinking tends to be orderly but dumb. Bottom-up thinking tends to be chaotic but smart.

Loved this, John. Good memories of a great little town and lifestyle.