During this season in which we remember how God came to earth in the form of a human baby, it’s right and proper to spend some time remembering His mother.

This year during Advent I read (and then re-read) Mary as the Early Christians Knew Her, by Frederica Mathewes-Green. I highly recommend it. In 175 short pages, Mathewes-Green provides text, context, and commentary for three ancient works about Mary. All three were new to me.

The first text is a narrative of Mary's early life. It probably started as oral tradition but was in print by A.D. 150 and became a kind of second-century bestseller. The second text is a brief prayer to Mary that was written down by A.D. 250 but probably existed much earlier in oral form. The third is known as the Akathist Hymn (circa 520 A.D.). Still sung annually by millions of Christians around the world, the Akathist Hymn celebrates the Incarnation and Mary’s special role in it.

This is how Mathewes-Green opens the book:

It is hard to see Mary clearly, beneath the conflicting identities she has borne over the centuries. To one era she is the flower of femininity, and to another the champion of feminism; in one age she is the paragon of obedience, and in another the advocate of liberation. Some enthusiasts have been tempted to pile her status so high that it rivals that of her Son. Others, aware that excessive adulation can be dangerous, do their best to ignore her entirely.

Behind all that there is a woman nursing a baby. The child in her arms looks into her eyes. Years later he will look at her from the cross, through a haze of blood and sweat. We do not know, could not comprehend, what went through his mind during those hours of cosmic warfare. But from a moment in St. John's account of the Crucifixion we know that, whatever else he thought, he thought about her. He asked his good friend John to take care of her. He wanted John to become a son to her — to love her the way he did.

It is not surprising that those who, in St. Paul's words, put on “the mind of Christ” would discover that they loved her too. Though we may picture the love of Mary as a medieval development, it actually goes back to the faith's early days. Those first generations of Christians did not include Mary in their public preaching of the gospel; they did not expose her to the gaze of the world. (Likewise, a celebrity today will object if reporters take photos of his family.) But when believers were gathered together in their home community, there Mary was cherished. As new members were brought into the body of Christ, they would also begin to share in the love the Christ child had for his Mother.

Many of us probably see ourselves somewhere in this introduction. I do. In multiple places, actually.

Growing up evangelical, we talked about Mary once a year. We emphasized her purity and obedience as the “handmaid of the Lord” (Luke 1:38). Beyond that, she wasn’t on our mind all that much. I assume this was more of an inherited rather than conscious corrective to what we perceived as the excessive Marian devotion of Catholics.

Later Mary became for me that “advocate of liberation.” Even today, hanging year-round in my living room, is a piece of art made by a pastor friend. It depicts a very pregnant Mary, fist in the air, proclaiming John Shelby Spong’s translation of the Magnificat, "My soul sings in gratitude / I'm dancing in the mystery of God…"

Early this year, I began earnestly exploring the lives, liturgies, history, and theologies of the earliest Christians. For some 1,600 years, Christians have proclaimed belief in one holy, catholic, and apostolic church. Yet today there are 45,000 denominations. I want to know: What is the kernel of faith that — in the words of St. Vincent of Lérins — “has been believed everywhere, always, and by all”?

Christians always and everywhere believed that Jesus was born of the Virgin Mary. In their earliest writings and art, we also see that, from the beginning, Christians had a special affection for the mother of Jesus.

The early church doted on Mary

The first text in Mary as the Early Church Knew Her is a delightful narrative of Mary’s childhood and early life. While never accepted as canon, it was nevertheless hugely popular as a devotional aid. (More than 100 surviving manuscripts have been found across at least eight languages.) The text tells the story of Mary’s birth to parents Anna and Joachim. She was raised in the Temple, where, filled with God’s grace, “she danced with her feet, and all the house of Israel loved her.” It tells the story of her betrothal to Joseph, a widower with children of his own. And it tells the story of the birth of Christ and the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt.

Throughout history, writes Mathewes-Green, “the most endangered member of any human society is a newborn girl. In most traditional cultures, and some modern ones, there are social and financial advantages to a son, but a daughter is welcome only when enough sons precede her. In too many times and places a little girl has not been welcome at all, regarded as pointless trouble and a waste of food.” Yet here we read about how Mary’s birth was met with rejoicing. When Mary’s mother Anna learns she has given birth to a girl, she says, “This day my soul is magnified.”

The earliest Christians seem to have been charmed by the story of Mary’s childhood, even as they protected and honored her after the crucifixion.

The early church asked for Mary’s protection

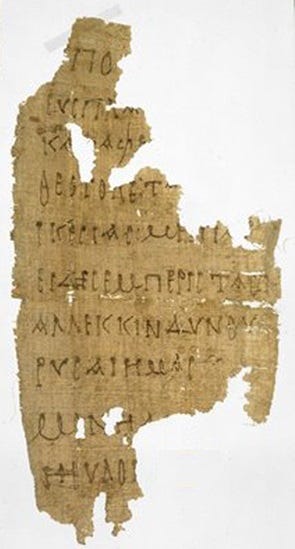

The second text in the book is a third-century prayer scribbled on a piece of papyrus the size of an index card. It included the line, “Do not overlook our prayers in the midst of tribulation…” In an era of brutal persecution, Mary was known as a prayer warrior on behalf of the church. Matthewes-Green writes: “Particularly when they were gathered for worship, the living were aware that they stood together with the departed who are alive in Christ. The ones who had been mourned…were then invisibly present among the ‘great cloud of witnesses’ (Heb. 12:1).” Our Christian forebears asked Mary and the saints to pray for them, the way we would ask a friend or relative to pray for us today.

The early church honored Mary as the Theotokos, the “Birthgiver of God”

Calling Mary the Theotokos or Mother of God doesn’t mean she existed before God or that she conceived the Trinity. As Mathewes-Green says, this title for Mary is actually a statement about Jesus: “It is designed to emphasize his divinity from the moment of conception.”

The third text in the book, the Akathist Hymn, was written in the early sixth century by St. Romanos the Melodist. It is comprised of 24 verses and structured as a series of greetings to Mary, building on Gabriel’s words at the Annunciation: “Rejoice, highly favored one” (Luke 1:28).

The hymn is soaked in Scripture. It is also stuffed with delicious paradoxes. One of my favorite sections begins, “Having seen this strange birth-giving, let us become strangers to the world and be brought over into heaven.” Then a couple lines later:

Wholly present among those below,

yet in no way absent from those above,

was the Word that cannot be encircled by words;

for thus did God condescend, and not merely descend to a different place.

He was born from a God-receiving virgin, who hears these words:

Rejoice, homeland of the boundless God,

Rejoice, doorway of sacred mystery,

Rejoice, dubious myth to the faithless,

Rejoice, confident boast of the faithful,

Rejoice, all-holy chariot of him above the cherubim,

Rejoice, all virtuous home of him above the seraphim,

Rejoice, for you draw opposites into harmony,

Rejoice, for you join childbirth with virginity,

Rejoice, you through whom transgression is annulled,

Rejoice, you through whom Paradise is opened,

Rejoice, key of the kingdom of Christ,

Rejoice, hope of eternal good things,

Rejoice, O Unmarried Bride!

Once upon a time, I might have recoiled at a couple of those lines — key to the kingdom? hope of eternal good things? — but this book helped me see them more clearly for what they are: poetic or affectionate overstatement, the counting of blessings, and nourishing food-for-thought.

For a long time, the Virgin Mary was a kind of Rohrschach test for me. When I looked at her at all, what I perceived probably said more about me than about her. This is why it is so actually eye-opening to learn how the earliest Christians saw her.

These early Christians weren’t necessarily smarter or holier than we are, Mathewes-Green writes, but they had a practical advantage: they were still living in the culture that produced the Christian Scriptures. It was their home, their language. “Their parents or great-grandparents had been alive when Christ walked the earth. The history of these things was the history of their backyard…”1 And from the beginning, she continues, Christians loved Mary “freely, deeply, and some way instinctively.”

Reading this book helped me love Mary more.2 A few days ago, I took my usual Sunday afternoon walk around the campus of Mt. Angel Abbey. For the first time, I felt drawn to the statue of Mary. I stood awkwardly for a moment surrounded by candles and rain-soaked flowers. Not knowing what else to do, I bowed my head in respect. If I’d had the Mathewes-Green book on me, I might have recited the third-century prayer, or lines from the Akathist Hymn. But I didn’t. Instead, these words came to mind:

Hail, Mary, full of grace,

the Lord is with thee.

Blessed art thou amongst women

and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

Holy Mary, Mother of God,

pray for us sinners,

now and at the hour of our death.

Amen.

I realized the Hail Mary neatly encapsulated so much of what I’d been reading in Mary as the Early Christians Knew Her — Mary’s blessedness, her ongoing intercession on behalf of the faithful, and her special role in the history of salvation.

It wasn’t until I was writing this post that I fully appreciated the title of this book, Mary as the Early Christians Knew Her. The earliest Christians did in fact know Mary. Some knew her personally, or were just one or two generations removed from those who did.

Interestingly, the more my love has grown for Mary the more my love and respect has grown for my own mother, a saint her in own right.

I finally got around to reading this (it was on my Kindle since you wrote it). Absolutely beautiful. I'm grateful you shared these thoughts.

This is so lovely, John! Thank you. You understand my book very well.