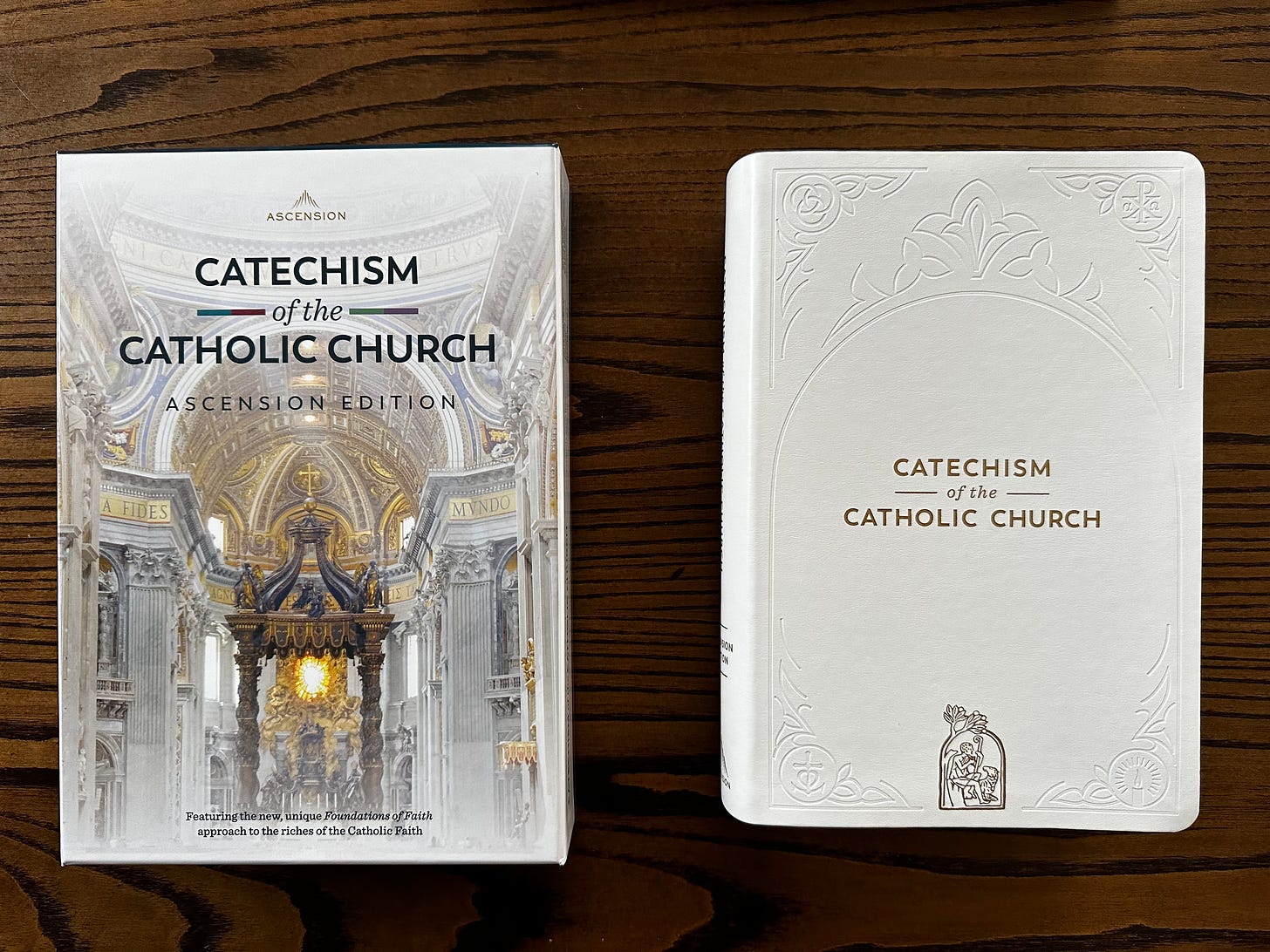

I’m a Protestant reading the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the first time. Specifically, I’m using the lovely Ascension Press edition, while listening through the Catechism in a Year podcast.

Here are my takeaways through Day 100:

1. The Catechism is a gift to the whole church

I don’t know how else to say it, except that I’m so grateful this book exists. It is a treasure-trove of Christian thought, our shared faith and history, and the hard-won insights of the ages.

Before I started reading the Catechism I assumed it was a classical text that had been modified and appended over the centuries. A kind of cathedral in words.

Nope.

I was 14 when the first edition was released. It was composed by a team of bishops while incorporating 24,000 suggestions from global church leaders, theologians, and other Catholics. Pope John Paul II said that “the harmony of so many voices truly expresses what could be called the symphony of the faith.”

2. The Catechism is both new and old

While the Catechism itself is new, it is made of ancient stuff. The “cathedral” may have been completed in 1992 but it is built of stones from around the world and across time.

The Catechism is rooted in Scripture (there must be thousands of Bible references), tradition (the writings of the Church Fathers and Mothers, the saints, etc.), and the teaching authority of the Church (something called the magisterium, a new word for me).

At the center of the Catechism, though, is Christ himself. As John Paul II said, “At the heart of catechesis we find, in essence, a Person, the Person of Jesus of Nazareth, the only Son from the Father…who suffered and died for us and who now, after rising, is living with us forever.”

It’s an interesting reading experience because the Catechism is a point of reference that manages — so far, at least — to always point away from itself. It doesn’t claim to be the final word, but rather it points to the First Word, Jesus, who is also the Last Word (see John 1 and Revelation 1).

Which brings me to my next thought…

3. The Catechism is the syllabus for a lifetime of study

The Catechism is replete with sources from Scripture, the creeds, liturgies, church documents, church councils, and ecclesiastical writers from the 2nd century through the 20th.

Through the Catechism I have been introduced to many Church Fathers and Mothers, and I’ve recently started reading a collection of early Christian writings edited by Andrew Louth.

4. I was taught a lot of misinformation about Catholicism

Growing up evangelical, I developed some wrong beliefs about Catholics and Catholicism. Some I was taught by others. Some I taught myself. Among these wrong beliefs:

Catholics don’t use the Bible.

Catholics added books to the Bible.

Catholics don’t evangelize.

Catholics worship Mary.

Catholics worship the saints.

Catholics aren’t Christians.

None of these things turn out to be true. This is based on what I’m encountering in the Catechism, as well as what I’ve seen in the lives of Catholic friends I’ve made over the last several years.

There are still some points on which I disagree with Catholic doctrine, but I can always see how a reasonable person can get there.

5. The Catechism is full of great writing

Perhaps this is comparatively unimportant, but I notice it as a writer and reader—the Catechism is full of great writing. For example, this sentence about Holy Saturday, which I read the day before Holy Saturday:

“It is the mystery of Holy Saturday, when Christ, lying in the tomb, reveals God’s great sabbath rest after the fulfillment of man’s salvation, which brings peace to the whole universe.”

I mean, come on! That sentence is rich both in style and substance. The day after God completed the work of creation, God rested. The day after Jesus says on the cross, “It is finished,” Jesus rests. That just stops me in my tracks.

6. Catholics are great at naming stuff

Here’s an example: evangelicals grow up hearing about “Original Sin.” But we never heard about — or at least never had names for — “Original Holiness” (humanity’s share in the divine life) or “Original Justice” (the state of harmony God intended between people, between humans and non-human creation, and in our own inner selves).

7. Chances are, Catholics got there first

A couple months ago I went hiking with a bunch of Catholic friends. (I am the designated Protestant in a local Exodus 90 men’s group.) The hike wasn’t arduous but parts of it were steep. I was also out of shape and fighting a cold. More than once the rest of the group paused to let me catch up and catch my breath.

One time, when I finally made it to the rest of the group, I said, “You Catholics have been waiting for Protestants to catch up for centuries. Don’t worry: we’ll get there.”

That’s also how I have felt reading the Catechism. More than once I have encountered ideas I’d “discovered” for myself some time before.

For example, some years ago I learned about the literal translation of our word “economy” (Greek: oikonomia) means “the law or management of the household.” This was such a revelation for me — and the theological and practical implications so interesting — that I wrote thousands of words about it for my Protestant brothers and sisters. Turns out, oikonomia is old hat in Catholic theology.

Part of this is my own fault for thinking there’s anything new under the sun. But there is also a hubris in Protestantism, and especially evangelicalism, that reminds me of the teenager who is shocked to discover that her parents once listened to Nirvana or Dylan or Bowie too. And maybe they still do!

I’m reminded of a passage from one of my all-time favorite books, Orthodoxy, by G.K. Chesterton:

I am the man who with the utmost daring discovered what had been discovered before…I did, like all other solemn little boys, try to be in advance of the age. Like them I tried to be some ten minutes in advance of the truth. And I found that I was eighteen hundred years behind it. I did strain my voice with a painfully juvenile exaggeration in uttering my truths. And I was punished in the fittest and funniest way, for I have kept my truths: but I have discovered, not that they were not truths, but simply that they were not mine. When I fancied that I stood alone I was really in the ridiculous position of being backed up by all Christendom. It may be, Heaven forgive me, that I did try to be original; but I only succeeded in inventing all by myself an inferior copy of the existing traditions of civilized religion. The man from the yacht thought he was the first to find England; I thought I was the first to find Europe. I did try to found a heresy of my own; and when I had put the last touches to it, I discovered that it was orthodoxy.

8. Protestants make it harder on ourselves than we need to

If you grew up evangelical as I did, you’d be forgiven for thinking Christianity experienced a 1,900-year theological drought between St. Paul and C.S. Lewis. I’m exaggerating but also kind of not. My evangelical friends and I typically had little knowledge of the saints of the past, the monks and mystics, the pastors and thinkers, the activists and artists who had penetrated deep into the heart of God and then told the rest of the world what they had seen there. We believed we were surrounded by a “great cloud of witnesses” (Hebrews 12) but we didn’t feel any great need to learn their names, or their stories, or their contributions to the faith.

Let’s imagine that growing in the grace and knowledge of God is like ascending a mountain. A thought I keep coming back to is that evangelicalism gives every new Christian a few tools — a pocket knife, some fishing line, and a roll of duct tape — and sends them off, survivor-style, to carve their own path up the mountain. This is, after all, a “personal relationship with Jesus.” (a phrase that never appears in Scripture). Again I’m exaggerating to make a point, which is that evangelicalism’s blind spots — individualism and a bias against tradition — make a life of discipleship harder than it needs to be. That’s why, when I read the Catechism, I keep encountering important “revelations” that had been discovered by the Church a thousand years ago.

For two millennia the Church has been mapping the mountain. The cartography of the spiritual life has been done with Scripture and tradition, but also trial and error, in good times and bad, through the experiences of the great and the lowly, by saints known and unknown, from St. Paul to St. John Paul II, from Thomas Aquinas to my neighbor Theresa who teaches RCIA classes at the local parish. The journey up the mountain may be mine to make but, as the Catechism shows, I’m not the first and I’m not alone. Once upon a time I was drawn to the new. More and more, I’m drawn to the ancient, the time-tested and weathered, the sturdy.

There are downsides to this of course. Sturdiness can easily become rigidity. Accountability must become more difficult too, as with the priest sex abuse scandal, when the apparatus of the Church covered up abuse, obstructed justice, and acted shamefully toward victims.

Change also comes slowly when you average an ecumenical council every 200 years or so. The Catholic Church seems to move at a different scale of time. (It reminds of the Ents in The Lord of the Rings.) I can only imagine how frustrating this must be for people working to make what they believe to be urgent changes from inside the Church.

Still, the wisdom found in the Catechism — along with the Church’s liturgical, spiritual, and artistic heritage — allows an ordinary person like me to ascend at least a little bit higher.

Once again I’m the Protestant following in Catholic footsteps. Don’t worry, I’ll get there.

9. Every Christian should read the Catechism

Those are just a few somewhat random thoughts inspired by my experience so far with the Catechism of the Catholic Church. I’m one-quarter of the way through. I really do think every Christian should read it. I recommend the Ascension Press edition, for functionality and aesthetics, but really any edition will do. You can also find the Catechism on the Ascension Press app. If you decide to read it too, tell me about your experience.