I was saddened to learn yesterday of the passing of Walter Brueggemann, the great Old Testament scholar. He was 92.

The author of more than 100 books—including The Land, Journey to the Common Good, Finally Comes the Poet, and The Prophetic Imagination—as well as hundreds of articles, Dr. Brueggemann was also generous in lending his name and reputation to other writers. He provided a thoughtful blurb for Slow Church, in which he described faith as “a practice of relational fidelity that cannot be reduced to contractual or commodity transaction. The authors ponder and reflect on this summons with both pastoral sensitivity and missional passion. Readers eager for an evangelically paced life will pay close attention to this advocacy.”

That was a kind thing to say.

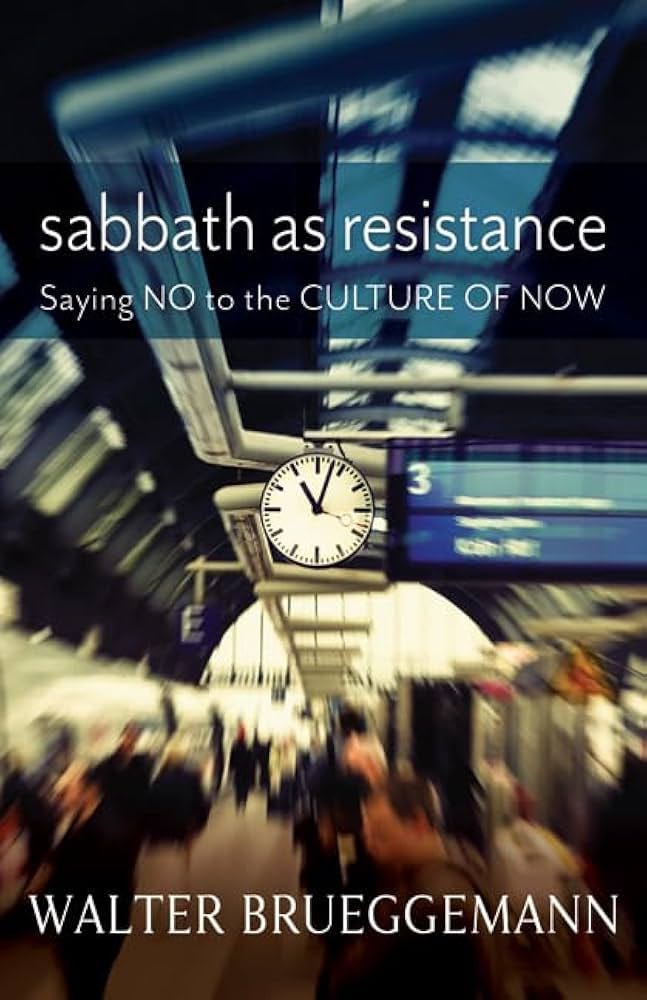

I met Dr. Brueggemann only once and only over the phone. Back in 2014, I interviewed him about his book Sabbath as Resistance: Saying No the Culture of Now. In that compact work, Brueggemann made the case that Sabbath isn’t an anachronism of the ancient past. Rather, “keeping the Sabbath” is a biblical commandment we ignore to our loss, perhaps now more than ever.

He describes Sabbath as both resistance and alternative. Resistance because it is the “visible insistence that our lives are not defined by the production and consumption of commodity goods.” But also alternative. “The alternative on offer is the awareness and practice of the claim that we are situated on the receiving end of the gifts of God.”

I spoke with Dr. Brueggemann on February 3, 2014. This was the day after more than 111 million people watched the Seattle Seahawks beat the Denver Broncos in the Super Bowl. At the time, it was the most-watched TV event in history. There was some irony in the timing, as you will see.

My conversation with Dr. Brueggemann was originally published in the Englewood Review of Books. I’m re-sharing it here with permission.

JP: It's been said before—and it seems true enough to say again—that the Fourth Commandment (“Remember the sabbath day, and keep it holy.” [Ex 20:8]) is the only commandment we routinely boast about breaking. How did we get to this point? Even American Christians brag about how incessantly busy we are.

WB: We are caught up in a culture of restlessness, a market ideology, in which the goal of life is to produce more and consume more. We consume more hours so we can produce more—and so we can be richer and more powerful and more effective and more well thought of. The market ideology is a rat-race that has infected us all.

JP: In the book, you describe a system of endless desire and endless production. You trace it from the advertising game, which you call the liturgy of consumerism, all the way down to politics and militarism and ultimately violence. And you say that all this contributes to a culture of anxiety. What’s the connection between the cycle of endless production and a culture of anxiety?

WB: The consumer culture defines everyone around us as a threat or competitor or as a rival for the same goods. Therefore, we don’t think of other people as neighbors; we think of them as people who threaten our property, our way of life, our possessions, and our futures. In order to fend them off, we resort to many forms of violence.

Violence becomes a function of individualism. “I don't want to share anything I’ve got, and I don't want anybody to get anything I've got. Therefore I have to protect myself.” I think that leads to violent policies. I think it leads to violent anti-neighborly actions.

JP: As you point out, this is why it’s so significant that the Sabbath texts specifically mention the widow, the orphan, the immigrant—all people who were less likely to be able to fend for themselves under the market ideology.

WB: That's right. That way of thinking in the Bible really makes it clear that we have an economic responsibility for vulnerable people. And of course that is a contradiction to the way we've organized our economy.

JP: In the book, you say that the Fourth Commandment serves as a bridge between the first three commandments, which are focused on God, and the last six commandments, which are focused on the community of neighbors.

WB: I learned this from Patrick Miller. He has argued that the Fourth Commandment has as its premise that God rested on the seventh day. So that refers back to the God of the first three commandments. The Sabbath command is that “you shall rest, and your neighbor shall rest.” And obviously the last six commandments are all about the neighbor. So in the Sabbath, what the God of the first three commandments and the neighbor of the last six have in common, is that they are both at rest. Neither of them are driven by excessive desire. Miller has made a very shrewd interpretation.

I’m reminded of a phrase in the book of Colossians, which says, “Do not practice greed, which is idolatry” [Col 3:5]. “Greed” is sometimes translated “covetousness.” So you’ve got in this verse the first two commandments, which are about idolatry, and then the Tenth Commandment about greed. It forms a nice envelope. Sabbath is a break with our idolatries and a break with our greed. It catches the main accents of all the Ten Commandments.

JP: I was struck reading the book with how closely the Sabbath is tied to the deepest questions of identity. You write, “The Sabbath rest of God is the acknowledgement that God and God's people in the world are not commodities to be dispatched for endless production…Rather they are subjects situated in an economy of neighborliness.” That gets to the heart of who we are, doesn’t it?

WB: That's right. What I’ve tried to say in the book is that the Sabbath commandment is not marginal or incidental. It is really defining for how we are to understand ourselves in the context of faith.

JP: That makes me rethink ever using the phrase “human resources” again.

WB: It’s kind of an oxymoron, isn't it?

JP: Reading that part of the book I was reminded me of something that Wendell Berry wrote in his essay, “Discipline and Hope”. He said, "If the Golden Rule were generally observed among us, the economy would not last a week. We have made our false economy a false god...So I have met the economy in the road, and am expected to yield it right of way. But I will not get over. My reason is that I am a man, and have a better right to the ground than the economy."

WB: Exactly. That says it. And what we’ve got now are “stand your ground” laws where we are free to kill anybody who doesn't get out of our way.

JP: The context in which the Sabbath commandment was given to Israel is that they had just been rescued by God from, among other things, the grind of Pharaoh’s system of endless production. How similar was Pharaoh’s system to the laissez-faire market economy we have now in United States?

WB: Well, it's obviously not an exact equation. But the way in which Pharaoh kept the Hebrew slaves at work at their brick quarters and made their working conditions harder and harder, withholding straw and all that, is roughly analogous to how our economy squeezes the working class. It keeps upping the production expectations and makes working conditions harder.

And it has the same reasoning as Egypt. Pharaoh had everything, but he didn't have enough. That's exactly the way our economy is working now. The people at the top of the pyramid have everything—and yet they don't think they have enough. Think of the personnel policies at Walmart. The Walton family of Walmart own half the world, but they have to keep squeezing the workers to get more because they don't have enough yet. That's how the system is shaped.

JP: It is interesting that the iconic image of a financial swindle is called a Pyramid Scheme.

WB: It strikes me as highly ironic. To talk about pyramids brings Pharaoh into the scene.

JP: When Sabbath is observed at all, it seems to most often be practiced at the individual level or at the level of the household. Yet Sabbath was a practice that helped give form and identity to the people of Israel both before and after they entered the Promised Land. You describe this in the book. For American Christians who are often spread out from others in their faith communities, does the Sabbath form us primarily at the individual level? Or can it form us at the communal level as well—in the local church, for example.

WB: I don't think that Sabbath can be practiced by isolated individuals. I think you’ve got to have a community around you that supports you. How do you tell your kid that he can't go to soccer practice on Sunday morning because it’s the Sabbath? You can't, unless you’ve got a number of other families telling their families that they can't go to soccer practice. It requires the discipline and support of a community that is committed to those values.

Not only do these people have to share the same values, to some extent they have to be committed to the same practices. The pressure of market ideology makes it almost impossible for a single person or single family to do this unless you're in a community that is generally supportive of it.

JP: Can Sabbath be a prophetic act? Reading your book, I couldn’t help but think about Sabbath as a modern way of telling the powers, “Let my people go!”

WB: That's exactly right. The word “exodus” means to exit or depart from a system. Sabbath is an act and it's a sign of departing from the values of that system.

JP: One final question. It was a little incongruous for me to be preparing for this interview yesterday. First of all, it was Sunday, the traditional Christian Sabbath. Second, it was Super Bowl Sunday. Super Bowl Sunday is a day known for the big game, of course, but also for its expensive high-profile commercials, and for the patriotic overlay that is draped over everything. That was in evidence yesterday. The Declaration of Independence was read before the game, and many of the commercials were heavy on patriotism.

At least twice in the book you are deeply critical of professional sports. How are professional sports related to that the culture of anxiety?

WB: Professional sports are essentially about money and power and—in the case of football and hockey—violence. I think you're right that there is an overlay of patriotism now; you have to sing the national anthem before every fool thing in the world. It's all tied to American virility, power, control, and mastery. The waving of the flag signifies all that, so it's all locked together with the dominant ideology of restlessness. The Super Bowl is the quintessential liturgy of that whole package of values.